He had quite a story. Bader was born in Vienna in 1924, and at 14 was sent to England (along with many others his age) to escape persecution. (His adoptive mother died in the Nazi camps, so this concern was extremely well-founded). In 1940 he was sent on to Canada, and he studied there at Queen’s – McGill’s quota for Jewish admissions kept him out of that university. He went on to Harvard for graduate work with Fieser, and afterwards found himself working in the chemical industry in Milwaukee.

Alfred Bader, a chemist, philanthropist and art collector who escaped the Holocaust in Europe and built a chemical company in Milwaukee, died Sunday. Bader was 94 and died peacefully, the family said. His wife, Isabel, was at his side.

After 80 years, survivors of the “Kindertransport” evacuation of Jewish children from Nazi Germany and elsewhere in Europe before World War II will receive compensation from the German government. The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, also known as the Claims Conference, said the German government agreed to pay each person still alive a one-time compensation of 2,500 euros ($2,800).

Kindertransport: Rescuing Children on the Brink of War runs through May 24, 2019 at the Center for Jewish History in New York.

Multi-specialty design studio C&G Partners has created a highly emotional and thought-provoking exhibition commemorating the 80th anniversary of the start of Kindertransport, the humanitarian mission that sought to rescue 10,000 refugee children from Nazi-occupied Europe in the years leading up to the Holocaust. Kindertransport: Rescuing Children on the Brink of War runs through May 24, 2019 at the Center for Jewish History in New York.

Female volunteers such as Marie Schmolka played a decisive role in the collaborative project to rescue beleaguered Jewish children.

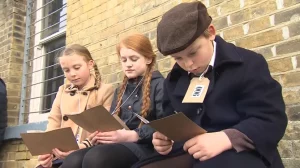

Children re-enact the Kindertransport journey 80 years on. Credit: ITV News Anglia

Schoolchildren across the region have been retracing the emotional journey of thousands of young refugees to mark the anniversary of the Kindertransport. Eighty years ago, the first Jewish children to flee the Nazis started arriving by ferry at Harwich in Essex. To mark the anniversary, students have re-enacted the journey at the stations of Harwich, Colchester, Ipswich and Manningtree.

Relics of this haunted but rarely examined chapter of the Holocaust are now on display in a small but stinging exhibit, “Kindertransport – Rescuing Children on the Brink of War,” a collaboration of the Yeshiva University Museum and the Leo Baeck Institute, that opened this week in Manhattan at the Leo Baeck Institute at the Center for Jewish History, through May 24, 2019.

Kindertransport – Rescuing Children on the Brink of War will be on view until May 24, 2019.

Nov. 26 several hundred people braved the rain to attend the opening reception of Kindertransport – Rescuing Children on the Brink of War. YU Museum, with the Leo Baeck Institute, has collected dozens of artifacts, ranging from teddy bears and letters to suitcases, games and a dress tailored for a young girl’s violin recital, with videos and audio to commemorate the rescue program undertaken only months after Kristallnacht in 1938 that brought 10,000 children to safety in the United Kingdom.

HIAS President and CEO Mark Hetfield addresses the Kindertransport Association at the Center for Jewish History in New York, December 2, 2018. Hetfield discussed the importance of remembering history and reminding the United States of its responsibility toward refugees. “We need your help in debunking this myth that nationalism is good and that a country should only look after its own…I need you to continue to speak out…we need you, we need your memory, we need your voice.”

This week is a particularly apt time to reflect on the legacy of US immigration policy in the 1930s. Eighty years ago this week, on December 2, 1938, the first group of Jewish refugee children arrived in Great Britain as part of a larger humanitarian effort to save Jewish children from the growing violence of the Nazi regime.

Clement Attlee, the Labour prime minister whose government founded the welfare state, looked after a child refugee who escaped from the Nazis in the months leading up to the second world war, it can be revealed. The then leader of the opposition sponsored a Jewish mother and her two children, giving them the confidence and authorisation to leave Germany in 1939 and move to the UK.

In recent months, I’ve learned that my life is bound together with two families who took enormous risks to save my father and my grandparents from the Nazis. What I have discovered about the rescuers is both wondrous and bleak. One family, the Furstenbergs, has thrived; another, the Mynareks, is gone, seemingly without a trace. My father, who had been rescued via the Kindertransport, was taken in by the Furstenberg family in Kalmar, Sweden.

A group of 60 Kindertransport survivors have urged the government to provide more routes to sanctuary for child refugees. ‘As former child refugees ourselves, we believe the UK government should give more children at risk the same life-saving opportunity that we had’

Gert Berliner, 94, tied the little stuffed monkey to his bicycle when he was a child in Berlin. Claire Harbage/NPR

The monkey’s fur is worn away. It’s nearly a century old. A well-loved toy, it is barely 4 inches tall. It was packed away for long voyages, on an escape from Nazi Germany, to Sweden and America. And now, it’s the key to a discovery that transformed my family.

“I liked him,” recalls my dad, who is now 94. “He was like a good luck piece.”

S Franklin Spira, with his mother, in an undated photo

Today is the 80th anniversary of the Novemberpogrome, or Kristallnacht. I was a 14 year-old boy then and my parents and I never thought of emigrating until the Kristallnacht, even though Jews were gradually being deprived of their rights before then. At that point, it became clear that my parents and I could no longer remain in our homeland.

Elsa Shamash and her brother before they came to the UK on the Kindertransport picture © Jewish Museum London

“The first train arrived on December 2 so the organisations and volunteers involved reacted very quickly, it was a fast response and an amazing effort to galvanise the British Home Office,” says Kathryn Pieren, curator of Remembering The Kindertransport, a new exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Camden Town

Organisers in Dorset of the campaign to allow three child refugees a year to settle in this county and all other local authorities have welcomed backing from county councillors. Dorset county councillors voted unanimously to give their support to the local safe Passage campaign which aims to replicate the so-called ‘KinderTransport’ initiative 80 years ago this year when Britain took in 10,000 child refugees fleeing Nazi persecution in Europe.

Even 80 years on from her flight from the Nazis, Elsa Shamash, 91, retains a strong German accent. She is a little deaf and her daughter helps her understand my questions. Her father was a pioneering radiologist and the family, which lived in Berlin, was wealthy. She and her brother Heinz were at private school before Adolf Hitler came to power, but then had to transfer to a Jewish school. Video www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=3xxfOKoblHk

Ruth Barnett, 83, was born in 1935, in a Germany that was already descending into Nazi tyranny. Her Jewish father was a judge who had been deprived of his post and frogmarched out of his court by the SS in 1933; her non-Jewish mother ran a cinema-advertising business in Berlin. “We had a brilliant future in front of us until the Nazis came to power,” she says.

His place on the Kindertransport was obtained with the help of Jewish organisation B’nai B’rith, and, aged eight, he left Fürth in March 1939, to Hamburg and then by ship to Southampton – a picture of the ship, the SS Manhattan which brought 80 refugee children to the UK, adorns the wall of his living room. The only English he knew was one sentence his parents had taught him: “I’m hungry; may I have a piece of bread?”